Published July 22, 2022

Viewing Major Taylor From All Sides

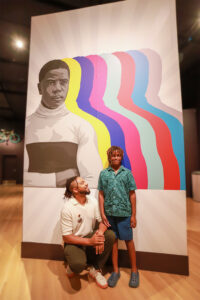

Artist Walter Lobyn Hamilton designed the entry to the Indiana State Museum’s new exhibit “Major Taylor: Fastest Cyclist in the World,” and he wants people in his eastside Indianapolis neighborhood to see his work. So outside his studio is a huge sign advertising the exhibit and making an offer: “Mention B Side Creative Campus” – that’s the project he’s building to provide subsidized living/workspace to artists and creators from various disciplines – “for free admission.”

Artist Walter Lobyn Hamilton designed the entry to the Indiana State Museum’s new exhibit “Major Taylor: Fastest Cyclist in the World,” and he wants people in his eastside Indianapolis neighborhood to see his work. So outside his studio is a huge sign advertising the exhibit and making an offer: “Mention B Side Creative Campus” – that’s the project he’s building to provide subsidized living/workspace to artists and creators from various disciplines – “for free admission.”

“It’s about access,” he says. “I thought the people who’d want to go see this exhibit, maybe they don’t know about it. I’m from the neighborhood, so I wanted them to be able to access it.”

The offer is limited to the first 200 attendees. Hamilton hopes that those who see the exhibit, which runs through Oct. 23, will appreciate the well-rounded story it tells of Major Taylor’s life – the championships he won, the racism he faced, the love of his family, the tough times he endured after he retired from competitive cycling.

Hamilton wanted the entryway – which he designed in collaboration with his 11-year-old son, Xavier, the museum’s Chief Officer of Engagement Brian Mancuso and Vice President of Experience Adam DeKemper – to tell “a much more nuanced, complex story” rather than “the Instagram version of the story” where everything was wonderful.

To the left, he has a wall of blown-up newspaper clippings that highlight Taylor’s feats and also expose the blatant racism of the day. To the right are a wall filled with blown-up letters and postcards written and sent by Taylor to his daughter, Sydney. In the center, Taylor is on a bike, cascading down an image of Indiana in which the state is shattering and dead in the middle.

The exhibit features many images of Taylor on a bicycle, of course, but it also shows him in a suit.

“The largest image of him is his obituary, so not to misremember the time that he became a champion and died bankrupt and unknown,” Hamilton said. “People dismiss a lot of different factors in the story and those things terrify me.”

Hamilton grew up in Indianapolis and became a full-time artist nine years ago. He’s concentrating these days on “vinyl record art” – reshaping and reconfiguring record albums. He said he knew a little about Taylor, mostly because of the velodrome named for him at Marian University. He didn’t know all the places Taylor went or the business choices he made, and he didn’t know the significance of Taylor’s daughter in his life.

Hamilton grew up in Indianapolis and became a full-time artist nine years ago. He’s concentrating these days on “vinyl record art” – reshaping and reconfiguring record albums. He said he knew a little about Taylor, mostly because of the velodrome named for him at Marian University. He didn’t know all the places Taylor went or the business choices he made, and he didn’t know the significance of Taylor’s daughter in his life.

“I thought that was the meat of the story – it’s her love that kept his legacy alive,” he said. “I learned how dedicated and intense he was. I didn’t know that he died broke and largely forgotten.”

The exhibit, ultimately, “is about love,” he said. “Love for the sport, love of competition, love for his daughter.”

But it’s also about how a champion can end up alone.

“I hope it is shocking and jarring,” Hamilton said. “I wanted to challenge and tell a holistic story.”