Published March 23, 2021

The Stories Behind Our Newest Experience

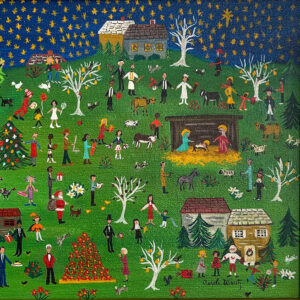

The newest experience at the Indiana State Museum is called “The Artwork of Carole Wantz: Collected Stories from Columbus, Indiana.” The key word is stories.

From 1975 to 1985, Wantz painted the upper echelon of Columbus society. She didn’t need to know what you looked like – the people in her pictures have no faces – but she had to know your story: What you liked to do, who your friends were, what was important to you. She captured those stories in her paintings.

Wantz is now 80, living in St. Louis, and getting renewed interest (and new commissions) from people in Columbus. This is her first museum exhibition.

In a phone interview, she shared some stories.

Wantz studied under Tony Vestuto, who taught at the Herron School of Art in Indianapolis and other places. She wanted desperately to be an abstract painter. But he pulled her aside and said, “I don’t want to hurt your feelings, but you’re terrible. I want you to create something from within yourself that has not been done a thousand times before. You’ve got to know your subject matter, and I believe you can do it.”

She spent six months at IU art library looking up painters, from Pieter Bruegel to Toulouse-Lautrec. When she found Grandma Moses, “I was just captivated and charmed by her. And I thought, that’s what I’ll do. I’ll paint my own stories.”

She painted her son’s hockey game and her daughter’s swim team, among other slices of life. Then she sold them at Fair on the Square. Wantz’s friend Christine Lemley brought her to the attention of her husband, Max, who was a member of the Columbus Chamber of Commerce. The chamber commissioned Wantz to create a painting for industrialist and philanthropist J. Irwin Miller.

To create the painting for Miller – which is the centerpiece of the Indiana State Museum show – Wantz interviewed people who knew Miller. She talked to five people and heard five different stories.

“Then I began having such self-doubt,” she said. “I thought, ‘How did I get this crazy idea that I could do this? He’s got a Monet and a Picasso. He’s never even heard of me.’”

She finally decided to paint the light, whimsical side of his life.

The night she unveiled the artwork for Miller, “I was just terrified.”

The way Wantz remembers it, “The painting was on an easel and there were all these men in business suits just staring at me. And I thought, ‘Just help me, please.’”

Miller looked at the painting, which contained vignettes from his life, and asked her to explain what she had painted.

“We were like a comedy routine,” she said. “I had been told that Mr. Miller never smiles, that he’s very serious, and I thought, ‘This is not who I was told he is.’ At the end, he leaned over and kissed me on the forehead and said, ‘Nobody’s ever done anything personal for me.’”

After that kiss, Wantz “was in a state of shock.” Miller asked her to write an explanation of everything in the painting and bring it to their house (which, these days, is a tourist attraction). When she did, she found her painting hung in the entryway. She expected it to be over the washing machine.

Miller’s approval helped Wantz land 150 commissions over the next 10 years, including Henry Schacht, chairman and chief executive officer of Cummins Diesel and, later, CEO of Lucent Technologies; Laurance “Laurie” Hoagland, president and CEO of Stanford Management Company and, later, chief investment officers for the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation; and James Baker, the president and chair of Arvin Industries.

Her fee for a painting: $350.

The usual process to paint people was to interview them first. She’d sit down and listen to their stories. “They told me what was important to them. For me to have this relationship with these incredible people and what they value not only inspired me but motivated me.”

Sometimes, though, people wanted to surprise a friend or family member with a painting. Wantz generally disliked “surprise” paintings. She remembers getting a commission from South Bend to paint a doctor. When the painting was unveiled, he was disappointed because the scenes didn’t reflect what was most important to him.

“When you’re talking about somebody’s life, the person will give you an entirely different perspective,” she said.

After leaving Columbus for St. Louis, Wantz continued as an artist, but in a different style. There, she has done many paintings that had been used as fundraisers. She said her work has helped raise more than $1 million.

She is looking forward to coming back to Indiana to see the exhibit and renew friendships with the people of Columbus.

“I’m thrilled. And what I’m thrilled about are all these people who have faith in me are all coming together. They’re all talking about this like it’s a family reunion. They’re emailing and calling and that’s such a gift. I can’t believe this is happening. I’m so touched.”