Staff Report

Earlier in April, seven Indiana State Museum and Historic Sites staff members set off on a mission: to find Ice Age remains in Indiana Caverns during the course of a six-day dig.

They were not disappointed.

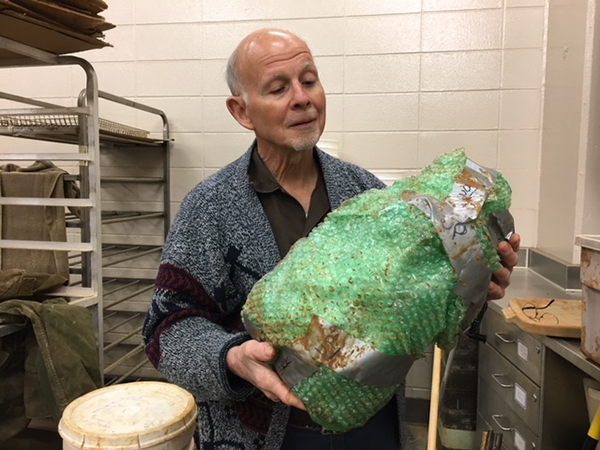

Inside a cavern with a 100-foot-high ceiling, museum staff found a gem right on the surface – a perfect flat-headed peccary skull, dating back about 40,000 years. It’s estimated that only a few dozen skulls of that caliber exist in the United States.

“It was an awesome dig,” said Ron Richards, senior research curator of paleobiology. “It was pretty majestic to walk into that work station every day.”

Even small digs like this one take months of planning, and Ron said they identified the dig site earlier in 2018 because of the skull they could see on the surface. Staff knew if that good a find could be seen on the surface, more bones were sure to lie beneath.

Over the next few months, museum staff will sift through the pounds of material to see what else was discovered. But, how does the whole dig process really work?

Take a look at the process in the photos below!

This dig was supported by the Randy and Deborah Patrick Paleontology Fund, and many thanks to Indiana Caverns for the collaboration on this project.

First, museum staff have to get to the actual dig site. In this case, main visitor paths could lead down to the dig site, which took about 15 minutes through a series of pathways and staircases. This means every break from digging had to be carefully planned – even bathroom breaks. Mud also made the trek difficult. The cave is still considered an “active cave,” meaning water is constantly dripping and creating new cave formations.

Next, staff had to set up the dig site. The area for this dig was only about 25 feet long by 3 feet wide. However, this dig site had many blocks of ceiling stone that had collapsed over time, and that stone had to be moved out of the way using wedges and other tools. Some stones weighed as much as 200 pounds.

After preparing the area, a screening platform had to be established as well. A tram was set up so that buckets of material could be transported up to the platform, where the soil was screened to separate out bones and other material. This was all done by hand, and visitors to the cave could actually watch the screening process.

After clearing the area and setting up the screening platform, the actual digging begins. Staff worked for six days from about 9 a.m. to 6 p.m., digging three feet into the ground in the established area. Great care had to be taken, since the bones are so delicate some would disintegrate if even touched too roughly – particularly for those that had been left out on the surface and exposed to the air for thousands of years.

As the dig progresses, buckets of material are transported up to the screening station using the tram to pull the buckets up. The material is also carefully labeled so staff know exactly which area of the dig site it came from. About 50 buckets of material were transported during the duration of this dig.

Up on the screening platform, the material is cleaned with water, and the debris separates through the window screen. What’s left are bones, rocks, and other large pieces of material. This material is collected for analysis, which takes place after the dig is complete. Some bones are able to be identified on-site as well.

Back at the museum, staff will go through all of the material over the next few months to determine what was found. So far it looks like mostly peccary bones, with mice, shrews, and rabbits as well. “Diagnostic bones” – bones we already have in our collection – will be used to compare against these bones, to determine what animals they belonged to. Radio carbon dating will also be done to provide a more exact estimate of the time period these bones are from.

Here, Ron Richards holds the very delicate – and securely-packed! – skull discovered during this dig. Museum staff will carefully clean it and preserve it over the coming weeks, preserving it indefinitely for the museum’s collection.