Published October 6, 2022

A Decorative Weapon in Selma’s Arsenal

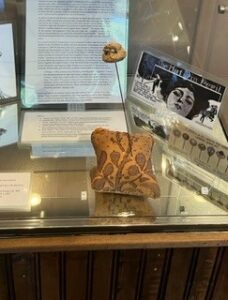

Each month, staff members at the T.C. Steele State Historic Site in Brown County display a favorite artifact from their collection and share its story. This month’s item, the Fabulous Hatpin, really caught our attention.

We’ll let Cate Whetzel, the historic site’s program developer, tell the story behind the object.

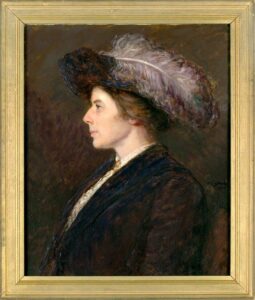

In honor of her birthday this month, October’s artifact highlight focuses on this hatpin owned by Selma Neubacher Steele. Hatpins emerged as an important accessory for women in the late Victorian era and early 20th century, subsiding only at the onset of World War I, and becoming obsolete in the 1920s, when bobbed hair and turbans became the fashion.

In honor of her birthday this month, October’s artifact highlight focuses on this hatpin owned by Selma Neubacher Steele. Hatpins emerged as an important accessory for women in the late Victorian era and early 20th century, subsiding only at the onset of World War I, and becoming obsolete in the 1920s, when bobbed hair and turbans became the fashion.

On average, hatpins (worn in pairs) were approximately 8 inches long, sharp, with decorated and ornamental heads. As ladies’ fashion hats and hair styles became wider, taller, and more elaborate, hatpins were used to secure the hat to a person’s head by pushing the sharp needles through the hat and hair. In a pinch, hatpins could be extracted and used in self-defense!

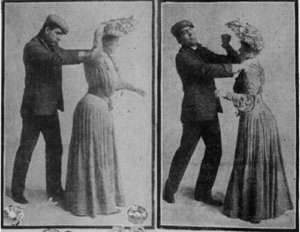

As women’s interests and activities moved beyond the home, girls and women of the late 1800s and early 1900s moved freely, unchaperoned, through their cities and towns. Men who were affronted by this freedom, or who wished to take advantage of a woman without friends around her, might take the opportunity to harass or attack a woman on her own. The hatpin became a valuable weapon for women against these “mashers,” period slang for predatory men. With the protection of the hatpin, women and girls were able to fight back when the need arose.

As women’s interests and activities moved beyond the home, girls and women of the late 1800s and early 1900s moved freely, unchaperoned, through their cities and towns. Men who were affronted by this freedom, or who wished to take advantage of a woman without friends around her, might take the opportunity to harass or attack a woman on her own. The hatpin became a valuable weapon for women against these “mashers,” period slang for predatory men. With the protection of the hatpin, women and girls were able to fight back when the need arose.

As a symbol of women’s independence, and as a bejeweled weapon legal and acceptable for women to carry, the hatpin was drawn, and even caricatured, in newspapers and novels. In L. Frank Baum’s 1904 “The Marvelous Land of Oz,” a new character is introduced: General Jinjur, a Munchkin girl who assembles an all-girl “Army of Revolt,” with the goal of revolution and regime change in Oz. Jinjur’s army is a parody of the Women’s Suffrage movement, and Jinjur’s soldiers overtake the Emerald City with their weapons of choice—two long needles—”knitting needles,” says Baum, but they also look a lot like hatpins.

As a symbol of women’s independence, and as a bejeweled weapon legal and acceptable for women to carry, the hatpin was drawn, and even caricatured, in newspapers and novels. In L. Frank Baum’s 1904 “The Marvelous Land of Oz,” a new character is introduced: General Jinjur, a Munchkin girl who assembles an all-girl “Army of Revolt,” with the goal of revolution and regime change in Oz. Jinjur’s army is a parody of the Women’s Suffrage movement, and Jinjur’s soldiers overtake the Emerald City with their weapons of choice—two long needles—”knitting needles,” says Baum, but they also look a lot like hatpins.

As the hatpin was seen more as a fearsome (albeit legal) weapon as much as a hair accessory, its notoriety was growing, and a desire to legislate the length of hatpins—from the United States to Australia—caused an uproar, though laws restricting the length of hatpins to no more than 9 inches were found to be practically unenforceable, with policemen unwilling to accost ladies to measure their hatpins.

As the hatpin was seen more as a fearsome (albeit legal) weapon as much as a hair accessory, its notoriety was growing, and a desire to legislate the length of hatpins—from the United States to Australia—caused an uproar, though laws restricting the length of hatpins to no more than 9 inches were found to be practically unenforceable, with policemen unwilling to accost ladies to measure their hatpins.

In Chicago, in 1910, a woman wrote this letter protesting potential legislation: “I always feel safe going home late at night with a hatpin available for protection. Before leaving a streetcar, I always carry a hatpin ready in my hand until I am safe within the door of my house.” She added: “Thousands of other women undoubtedly can speak from their experience of how a stout hatpin has been an effective defence in times of danger.” A raunchy music hall ballad of the time, “Never Go Walking Out Without Your Hat Pin,” echoed the sentiment. (Natasha Frost).

In Chicago, in 1910, a woman wrote this letter protesting potential legislation: “I always feel safe going home late at night with a hatpin available for protection. Before leaving a streetcar, I always carry a hatpin ready in my hand until I am safe within the door of my house.” She added: “Thousands of other women undoubtedly can speak from their experience of how a stout hatpin has been an effective defence in times of danger.” A raunchy music hall ballad of the time, “Never Go Walking Out Without Your Hat Pin,” echoed the sentiment. (Natasha Frost).

Society’s perspective on a woman’s place, once referred to as “The Woman Question,” was shifting in favor of women’s independence, away from depicting women as comic, dependent figures, and instead showing their fight against harassment as heroic, moving woman from object to subject, of her own body and her own story. (Karen Abbott).